|

Thomas Garrett:

The

News Journal, August 21, 1997

Savior of Slaves

The Wilmington abolitionist who dared to turn the other cheek and make

friends with his enemies gradually gets his due as a

Delaware hero.

By Gary

Soulsman

Staff

Reporter

At his death in 1871, Thomas Garrett was Wilmington’s best-known

citizen, eulogized as one of “the best men who ever walked on

earth.”

Few know

his name today. Those who do say he was motivated by a placid

self-sacrifice and courage that made him a genuine hero.

At

personal risk he gave refuge to 2,700 African-Americans fleeing

slavery – more than Harriet Tubman in her 19 trips leading

runaway slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

And a

growing chorus of Delawareans say the life of the 19th

century iron merchant and abolitionist, who lived at 227 Shipley

St., could lure tourists to Delaware and inspire the young – if

his deeds were cherished and his life memorialized with statues

and buildings.

During

Thomas Garrett’s life he was a much loved figure,” says Harmon

Carey, executive director of the Afro-American Historical

Society of Delaware. “It’s unfortunate few remember him because

this is not a black or white issue. It’s a matter of knowing an

important Delawarean.”

How is

it, local historians ask, that few native Delawareans even know

Garrett’s name? It’s a good question to ask today since Garrett

was born on this date in 1789 in Upper Darby, Pa.

His story

is the stuff of American legends. In his 20’s, historians say,

Garrett had a conversion experience comparable to that of Saul

on the road to Damascus, galvanizing his will against the

abomination of slavery. In 1822 he relocated in Wilmington,

where he was so successful in his abolitionist efforts that

African-Americans called Garrett the black man’s Moses.

Writer

Harriet Beecher Stowe even modeled one of her fictional heroes –

Simeon Halliday – after Garrett in the 1852 antislavery novel

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

“He was

truly a national figure,” says Barbara Benson, director of the

Historical Society of Delaware. “His moral vision was to

eliminate slavery and he devoted himself to that purpose at

enormous personal sacrifice.”

On

separate occasions, he was thrown from a train and attacked by

killers, but Garrett would not be deterred. He is even said to

have invited the would-be killers into his house for a meal

after he challenged their attack.

Later

Garrett was tried in New Castle federal court for helping

runaway slaves and was fined such a princely sum he had to sell

his house and possessions. But friends came to his aid and

Garrett was only determined to fight slavery, which he did for

close to 50 years – long enough to see it abolished.

When he

died at almost 82, crowds filed past his casket in his home.

Then to honor what he had done for all African-American people,

eight black men carried his coffin on their shoulders across

Wilmington’s Quaker Hill, where 1,500 mourners crammed into the

Friends Meeting House for the funeral.

“Children

are hungry to know there was a man in Wilmington this heroic,”

says Vivian Abdur-Rahim, director of the Harriet Tubman

Historical Society in Wilmington. “Why is it the state doesn’t

fully recognize the achievement of a person who has given their

life for others?”

As

director of the state historical society, Benson says people

don’t know nearly enough about local history. Newcomers often

fail to learn about their new home and she believes many

students are only taught a local history unit in fourth or fifth

grades.

Nationally, only in recent years had the Underground Railroad

started to get the attention it deserves. That recognition has

been slow to come because these heroes, though inspirational,

were overshadowed by the Civil War and kept few records, their

activities being clandestine, says Benson.

To make

Garrett’s story better known, Rahim has been leading tours of

Underground Railroad sites on the Delmarva Peninsula for seven

years.

Garrett:

Famed abolitionist made friends out of enemies

Both she

and Thomas Colgan of Arden believe that Garrett could be an

important symbol to a city troubled by drugs and killings. They

are among a small group of Delawareans devoted to the memory of

Garrett, working to make his life known.

For example:

Colgan

portrays Garrett for special tours of the Quaker Hill cemetery.

Colgan has also written a short play about the collaboration of

Garrett and Tubman after she escaped slavery and led others from

bondage. Colgan is a Quaker who believes the Society of Friends

needs the leadership of Garrett.

The State

Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs has created a free

exhibit at the New Castle Court House, in Old New Castle,

comparing Garrett and William Penn, two Quakers who left their

mark on Delaware and the region. Cynthia Snyder, who supervises

the site, says guides also give special tours telling about

Garrett’s 1848 New Castle trail with fellow abolitionist John

Hunn.

Rahim is part

of a committee to raise $250,000 for Quaker Hill statues of

Garrett and Tubman. Rahim believes Garrett’s life would make a

compelling film and is writing letters to see if she can

interest a Hollywood producer. She also advocated changing the

slogan of the city from “A Place to Be Somebody” to “The Last

Great Stop for Freedom.”

The Historical

Society of Delaware is planning a high-tech display on Garrett

in a new permanent exhibit on First State figures that will open

in 1998.

MBNA Corp.

recently announced the donation of the old Allied Kid tannery at

11th and Poplar streets in Wilmington for a new

African-American museum that would highlight many contributions,

including those of Garrett.

Bayard Marin,

president of the Quaker Hill Preservation Foundation, says

Garrett’s legacy and the architecture of the older section of

the city could make Wilmington a mecca for African-American

tourists fascinated by their history.

He proposes

restoring the Quaker Hill home built by Garrett’s son Elwood on

Washington Street, making it an Underground Railroad History

Center. The building is one of at least 19 Quaker Hill

properties Marin wants the foundation to restore.

A man of deep convictions

A stocky

and reverent man from a Pennsylvania family of millers, Thomas

Garrett was taught the Quaker belief in “the divine presence in

the human soul,” an idea that looked at each person as equal

before God.

Historian

James McGowan writes that the most important experience of

Garrett’s life occurred in 1813 when the young man returned to

his Upper Darby home to find that a free black servant had been

kidnapped by men intent on selling her into slavery.

Garrett

set off to Philadelphia in pursuit. On the road, he witnessed a

light brighter than the sun. He told friends something about the

light touched his soul and spoke of the horror of slavery.

“A man’s

duty is shown to him and I believe in doing it,” he said after

rescuing the servant.

In moving

to Wilmington in 1822 – where he opened a business selling iron,

coal and steel – he became part of a network of abolitionists

(often called the Underground Railroad) giving food, clothes and

a haven to black people who fled Southern plantations.

When they

reached Garrett’s home, slaves had almost won their freedom

since Pennsylvania was a non-slaveholding state. But Garrett’s

activities exposed him to danger, writes McGowan in “Station

Master of the Underground Railroad.”

Slave

owners, who paid between $500 and $2,000 for slaves, said they

considered them property and Garrett’s harboring runaway slaves

was against the law – like receiving stolen goods. Still,

Garrett did not hide his activities, though other abolitionists

were known to have been beaten and their houses burned. Garrett

sought to “disarm with candor,” according to McGowan.

One story

gives a hint to Garrett’s character. A slaveholder turned up at

his house one day threatening to kill Garrett if he ever came

South.

Garrett

replied that he would make the journey soon and would call on

the man – which he did. The two are reported to have become

friends.

On

another occasion the Maryland legislature was proposing a

$10,000 bounty on Garrett because he had aided so many slaves

escaping Maryland plantations. Garrett wrote the legislators

saying if they made the sum $20,000 he would turn himself in for

the reward.

He was

bold to the point of being fearless. Even while his house was

watched by slave catchers, he would walk slaves out the front

door in the guise of bonneted Quaker women. He believed God was

on his side and he would not fail.

He rarely

did. Even his 1848 trail for aiding an escaped family of slaves

from Queen Anne’s County, Md., was a triumph. Samuel Hawkins,

his wife and children were caught near Middletown -- before

they reached Garrett – but he used a loophole in their arrest

warrant to free them and see them to safety.

For

frustrating the slave catchers, Garrett, then 60, was tried in

New Castle’s U.S. District Court and fined $5,400. After the

verdict, he spoke passionately about his commitment to fight

slavery and all that ever stopped him was the Civil War.

Near the

end of his life, when blacks had been freed and given the right

to vote, Garrett said: “I have lived to see my Divine Master’s

will well accomplished. My mission’s ended. I am ready to go.”

TO

LEARN MORE…about Thomas Garrett:

Vivian

Abdur-Rahim, Director of the Harriet Tubman Historical Society,

is available for tours of the Underground Railroad. The New

Castle Court House on Delaware Street in Old New Castle has an

exhibit on Garrett and a special tour dealing with his U.S.

District Court trial. (302) 323-4453

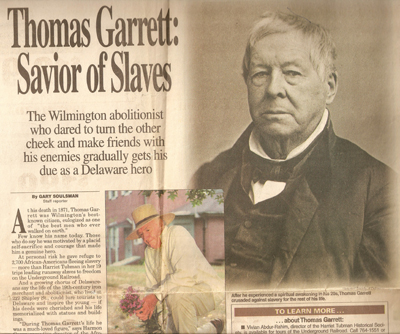

Photo:

Thomas Colgan of Arden visits Garrett’s grave marker at Quaker

Hill cemetery. Colgan portrays Garrett during special tours

there. The News Journal/Bob Herbert, Photographer. |